Abstract

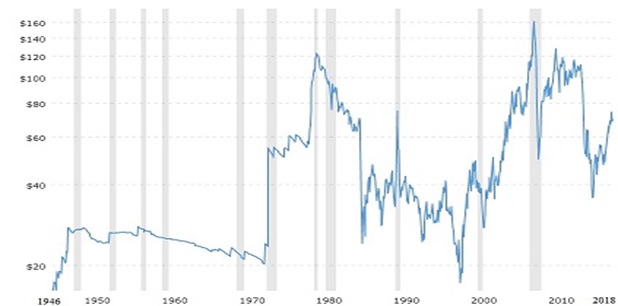

This paper examines the impact of endogenous and exogenous shocks on macroeconomic fluctuations. It explores various aspects of fiscal and monetary policy, their effects on economic growth, and the role of external factors such as oil prices in the emergence and stabilization of economic fluctuations. Examples of significant economic shocks caused by sharp changes in oil prices from 1946 to 2018 are provided, and their impact on the economies of oil-importing and oil-exporting countries is analyzed. The main focus is on the relationship between economic fluctuations and short-term shocks, as well as the mechanisms through which oil shocks affect aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

The economic literature presents various studies on the impact of fiscal and monetary policy on economic growth. Some research suggests that fiscal policy can explain up to 30% of cross-country differences in economic growth [1, 2]. The role of fiscal policy is particularly noticeable in developed countries, where it helps stabilize economic fluctuations. Components of fiscal policy, such as social protection systems, subsidies, and transfers, play an important stabilizing role during economic fluctuations.

However, there are conflicting results regarding the impact of fiscal policy on economic growth. Some studies indicate that fiscal policy may exert a "crowding-out effect" on private investment and lose its stabilizing role during periods of economic fluctuations [3]. Macroeconomic policy aimed at achieving economic growth does not always help reduce the impact of economic fluctuations and may even exacerbate them.

The role of monetary policy in stabilizing fluctuations is also a subject of study. Some research indicates that the impact of monetary and fiscal policy on investment, consumption, and production is minimal [4]. Comparative analysis of empirical studies shows that it is impossible to unequivocally confirm the role of fiscal and monetary policy as stabilizers of macroeconomic fluctuations.

Calvo G. and Vegh C. in their studies show that external shocks play an important role in the emergence of economic fluctuations [5]. They studied the impact of external shocks on developing countries during the period from 1988 to 1991, revealing significant effects of U.S. monetary policy on the financial systems of these countries and the creation of serious economic fluctuations [6]. Studies by F. Ghanova on a sample of Latin American countries also confirm that developing countries are more sensitive to external shocks compared to developed countries [7].

There is also an opinion that external shocks do not play a significant role in creating macroeconomic fluctuations. N. Loayza and C. Raddatz empirically show that structural characteristics, such as economic openness and market flexibility, can stabilize the impact of trade condition shocks on aggregate output [8]. The literature also examines shocks from U.S. monetary policy and oil price shocks as major sources of economic fluctuations. B. Mackowiak in his studies divides external shocks into two categories: "U.S. monetary policy" and "all other" shocks. Using a structural VAR model, he concludes that 85% of price changes are caused by exogenous shocks [9].

Oil prices are an important factor influencing economic fluctuations. Oil is used as a primary energy source and significantly impacts the production process. It is also unevenly distributed across regions and traded in U.S. dollars, making its price sensitive to economic fluctuations. The extent to which oil price shocks affect economic activity depends on whether a country is an oil exporter or importer. An increase in oil prices brings income to oil-exporting countries but increases costs for oil-importing countries, and vice versa.

Studies show that a constant inflow of oil revenues can lead to increased government spending and the weakening of the non-oil sector in oil-exporting countries. Increased oil revenues strengthen the national currency and promote imports of non-oil products. A decrease in oil prices can seriously affect the economies of oil-exporting countries, causing currency depreciation and economic problems, as seen in Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan in 2013. Such phenomena caused by rising oil prices are known as the "Dutch disease."

Oil price shocks also impact oil-importing countries by increasing production costs and reducing national income, leading to higher inflation and budget deficits. The impact of oil price shocks on economic fluctuations is explained by shifts in the aggregate demand curve in both oil-importing and oil-exporting countries.

Over the past 150 years, oil shocks have occurred several times and have significantly influenced economic activity. The first oil shock occurred in 1862-1864 in the U.S., triggered by the Civil War. The importance of oil increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the invention of internal combustion engines and the development of electric power. The expansion of automobile production also significantly increased the demand for oil, leading to higher prices.

After World War II, rapid economic growth once again increased the demand for oil, causing further price shocks. In 1952-1953, actions related to the U.S.-Korean War and the nationalization of Iran's oil industry had a significant impact on the global oil market. The Suez Canal crisis in 1956-1957 also caused another oil shock.

Figure 1. Oil Prices and Global Market Shocks from 1946 to 2018

In 1973-1974, OPEC sharply raised prices twice, significantly impacting global economic activity. The Iranian Revolution of 1979-1980 and the Iran-Iraq War in subsequent years also influenced oil prices. From 1981 to 1986, oil prices fell sharply. Despite a brief price increase in 1990-1991, low oil prices persisted. In 1997-1998, the economic crisis in East Asian countries substantially reduced oil demand, but rapid economic growth resumed in these countries in 1999-2000, sharply increasing oil demand.

In 2003, the Second Gulf War again sharply increased oil prices. This increase continued with short-term shocks until 2007-2008. The global financial crisis of 2008-2009 significantly impacted oil prices. The downturn in economic activity also substantially reduced oil demand.

Oil price shocks in the global market can be characterized as both a result of overall economic activity and a factor influencing it. The occurrence of such shocks always has a strong impact on the economies of both oil-importing and oil-exporting countries.

Therefore, it can be noted that:

1. Economic fluctuations and short-term shocks are interconnected.

2. Economic fluctuations are changes in economic activity resulting from aggregate demand and aggregate supply shocks.

3. Oil shocks affect economic activity by altering aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

Reference:

1. Sims, C.A. Macroeconomics and reality // Econometrica Journal, - 1980. 48(1), - p. 1-48.

2. Bouakez H., Cardia, E. F. Ruge-Murcia, The transmission of monetary policy in a multi-sector economy, - 2009. 50 (4), - p. 1243-1266.

3. Majid Al-Moneef. Partnership for Arab Development / Majid Al-Moneef, - Vienna, Austria: A Window of Opportunity held at OFID, - 2006. p.48.

4. BP Statistical Review of World Energy / Energy Outlook, - 2019. – p. 60 https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2019-full-report.pdf

5. Canova, F. The transmission of US shocks to Latin America // Journal of Applied econometrics, - 2005. 20, -p.- 229-251.

6. Shin, Y. Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ardl framework / Y.Shin, B. Yu, M Greenwood-Nimmo / In Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt, - New York: NY:Springer, - 2014. p. 281–314.

7. Corden, Max W. J., Neary, P. Booming Sector and De-Industrialisation in a Small Open Economy // The Economic Journal, - 1982. Vol. 92, No. 368, -p. 825-848

8. Le, T. H., Chang, Y. Oil price shocks and trade imbalances // Energy Economics, - 2013. 36, - p. 78-96.

9. Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira, 2013. The value of the exchange rate and the Dutch disease // Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, - 2013. vol. 33, n 3 (132), - p. 371-387

|